Rejection slips are a natural part of sending out work to magazines; in fact, rejection is the norm. If each magazine only takes 1-10% of what it receives, the odds are always against you. Except when a piece of your work sparks something in the editor and you get lucky.

Rejection slips are a natural part of sending out work to magazines; in fact, rejection is the norm. If each magazine only takes 1-10% of what it receives, the odds are always against you. Except when a piece of your work sparks something in the editor and you get lucky.Recently, I noticed a trend in the rejection notices: the wording is nicer, soothing, of the variety "It's not you, it's me." Did something change in the past three decades? I remembered a blunt "Thanks, but no" type of rejection. I was curious, so I pulled out my file of actual paper rejection letters to compare them. These are only from 2009 to 2013. Shorter ones are from some well-known publications: sometimes a little slip, sometimes a full page with just a few lines. Longer letters tend to ask you to subscribe. I'm really fine with yes or no at this point, but how the rejection is worded can make a difference, particularly if you are just starting out.

A very nice letter from Zyzzyva that begins, "Gentle writer."

And includes:

"Do not be discouraged by this or any other momentary setback.

The road is long; the struggle must go on."

And a little "Onward" handwritten from Howard.

The New Yorker is to the point:

"We regret that we are unable to use the enclosed material.

Thank you for giving us the opportunity to consider it."

Fiction, at City College of New York writes thank you and

"after careful consideration, the editors were not able to accept your work."

The rest of the letter explains why they include no other response and that if you

subscribe and you say so, your work will be looked at more quickly.

"The return of your work does not necessarily imply criticism

of its merit, but may simply mean that it does not

meet our present editorial needs."

Seems reasonable to me.

"It is not quite right for the Bellingham Review but we wish you the very best in

placing your submission elsewhere.…We understand

the success of our journal depends on the submissions we receive

and hope you will consider submitting to us in the future."

It is always hard to know what is "quite right."

Calyx, in Oregon includes,

"At least two editors have read your work and found

that we are unable to use your submission to the Journal."

I'm not sure I feel better that two editors rejected it.

Chicago Quarterly Review: "We're sorry that it does not

meet our needs, and we wish you the best of luck in

placing it elsewhere."

Elsewhere, okay.

Elsewhere, again.

"…we are not reading new poetry at this time."

"…we can't use it in The Threepenny Review at present."

Or any other time, really. Don't make the mistake

of resending something that has already

been rejected.

"…sorry to report that your manuscript does not suit

the present needs of the magazine."

The "present needs" makes more sense and doesn't

imply the future as much.

Ah, McSweeney's. I think this is my favorite because of its upbeat nature.

(Or maybe it's the design of the card. Or the typeface.)

The first paragraph begins with "Greetings" and thanks you

and tells you why you are needed as a submitter.

The second paragraph: "Unfortunately, we can't find a

place for this piece in our next few issues. Nevertheless,

please feel free to submit more work in the future. Our

themes and tastes change, and we are grateful for the community

of readers and writers that keeps us busy. Thanks again for

your efforts and for letting us see your work."

Okay, maybe I do care how I get the news.

Crazyhorse in South Carolina was nice, too.

A little humorous with the "…and we're sorry that this

particular story, selection of poems, or essay wasn't a good fit…"

I like the obvious impersonality of it.

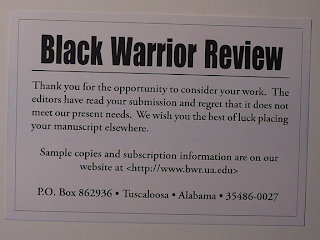

thank. opportunity. regret. needs.

"Though your manuscript has not found a place with

The Atlantic, we thank you for the chance to consider

it. Best of luck placing it elsewhere."

It feels a little better being worthy of a full page,

rather than a fortune from a cookie.

But of course, it's not personal!

"We are sorry to report…"

and

"we wish you the best in placing it elsewhere."

No need to report.

The Sun says thanks and sorry and not right.

The two paragraphs that follow are earnest,

nice to read, but not entirely necessary. The first:

"This isn't a reflection of your writing. We pick perhaps

one out of a hundred submissions and the selection process

is highly subjective, something of a mystery even to us.

There's no telling what we'll fall in love with, what we'll

let get away."

New editor at Zyzzyva. But still a very encouraging form.

And, the gold star of rejections: a handwritten note.

They enjoyed reading my piece, anyway.

This one has a typo.

"Athough (sic) we will not be publishing your work

at this time and are sorry to disappoint you,

please be assured that your manuscript was read

carefully by editors and trained screeners."

Carefully. Maybe.

If you read back issues of the magazines before you submit—which all editors recommend you do—you may find some similarities in style or tone of the work accepted, or you just may continue to be deeply baffled. Many magazines want a point of view that doesn't come from a generic middle-class lifestyle. Some want the personal, first-person essay style, wanting to hear something "real" or "authentic, " not have the work be about "characters." Others love the surreal and strange, the just-on-the-edge of mean, or just the edgy. I've seen quite a bit of jam-packed adjectives and metaphors as the desire of some publications. It's always hard to tell if your work "fits." And you may not even like the idea of your work "fitting," wanting your work to speak for itself on its own terms. Be aware of what is out there, but don't try to write in someone else's style. (More on this in my post, "A Crazy Little Thing Called Competition.")

If you are still curious about what editors want, I recommend the article, "What Editors Want" by Lynne Barrett. It's perfect.

What to do with your rejection slips? Hang onto them. Maybe next year you can sew them onto a sheet and be a Ghost Writer for Halloween.

Comments

Thanks for an enjoyable blog read.

Or maybe I'm still in that strange place writers go when their work is failing? (wink)